Trace vapour detector using sniffer bees

Honeybees have an acute sense of smell, can be trained quickly, and are relatively inexpensive to maintain. They are capable of detecting extremely low concentrations of volatile compounds — down to parts per trillion for certain chemicals — with high specificity. These characteristics make them a compelling biological sensing mechanism for trace vapour detection, with potential applications in explosives screening, agri-food quality assurance and selected diagnostic use cases.

When presented with food, bees naturally exhibit a Proboscis Extension Reflex (PER). Through conditioning, this response can be reliably triggered by other specific stimuli, such as the presence of a particular volatile compound. This behavioural response forms the basis of Inscentinel’s VASOR technology (Volatiles Analysis by Specific Odour Recognition), allowing biological olfactory capability to be interfaced with an engineered detection system.

The challenge

The UK Home Office explored the use of Inscentinel’s VASOR technology for screening people and luggage for trace residues of explosive materials. When I became involved, a laboratory proof-of-concept system already existed, using a camera and PC-based image analysis to detect the PER from three bees.

“Marc not only built a cost-effective functional prototype, but actively promoted our technology with potential clients and partners”

The task was to translate this laboratory setup into a self-contained, hand-held prototype suitable for field trials in airport terminals and aircraft cargo holds. The device needed to be portable, accommodate up to 36 bees, and be operable by airport security personnel. This imposed a set of tightly coupled constraints: the system had to be compact and lightweight, battery-powered, operate without a camera or PC, and generate its own clean and controlled airflow.

Together, these requirements ruled out a direct scaling of the laboratory setup and drove the development of a fundamentally different system architecture.

System architecture

To meet these constraints, the system architecture was organised around a small number of tightly integrated functions:

- Positioning the bees in the airflow, switched between filtered and unfiltered ambient air

- Detecting and interpreting PERs for 36 bees, providing an easily configurable user interface

- Providing rechargeable battery power to the system

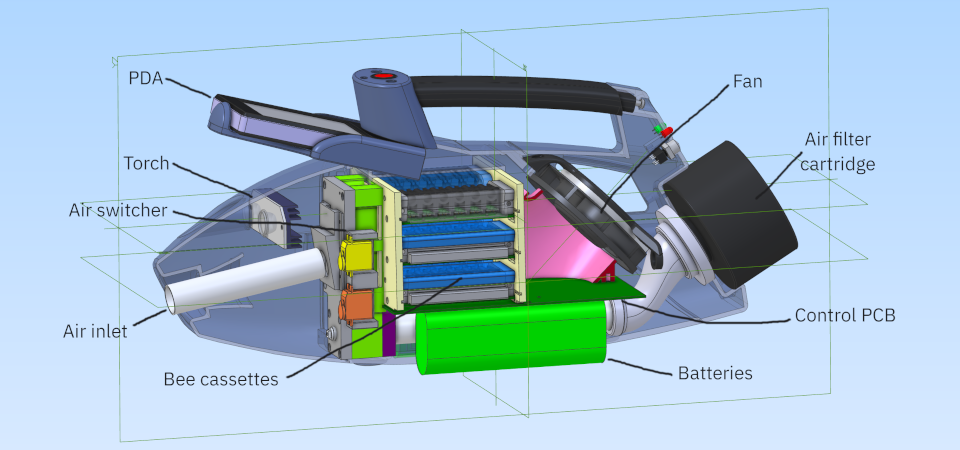

The image below shows the main elements of the VASOR system and how these functions were realised.

Beeholders

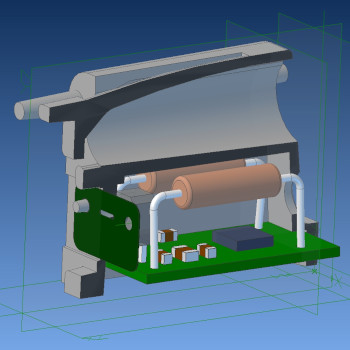

Each bee is held in an individual beeholder: an injection-moulded restraint incorporating heating resistors (bees need temperatures above 10 °C), a microcontroller for identification and traceability, and a phototransistor to detect occlusion of an infrared beam by a PER.

Early experiments showed that the beam was also interrupted by bees moving their antennae. Distinguishing meaningful PER events therefore required interpreting the signal shape: deep, slow drops in intensity indicated a PER, while shallow, fast variations corresponded to normal movement.

Beeholder electronics were embedded in potting compound to allow cleaning in a dishwasher.

System hierarchy

Although the Home Office trials converged on a design using 36 bees, the system was deliberately structured to remain adaptable to other portable or stationary applications. We adopted a hierarchical system architecture that could be expanded or reduced without major redesign.

Thirty-six beeholders were grouped into six cassettes of six holders each. Each cassette contained electronics to communicate with individual beeholders and with the main VASOR system, allowing alternative configurations with fewer or more cassettes to be realised quickly. Cassette PCBs had conformal coating to enable dishwasher cleaning.

For the Home Office prototype, the user interface ran on a Compaq PDA, a conveniently portable Windows CE device. We also added an integral torch for use in in aircraft luggage holds.

Airflow

Bees do not exhibit a PER when the composition of the air changes gradually; a step change is required as a trigger. In the laboratory this was achieved by switching between clean air and headspace air, but in the portable prototype no clean air supply was available.

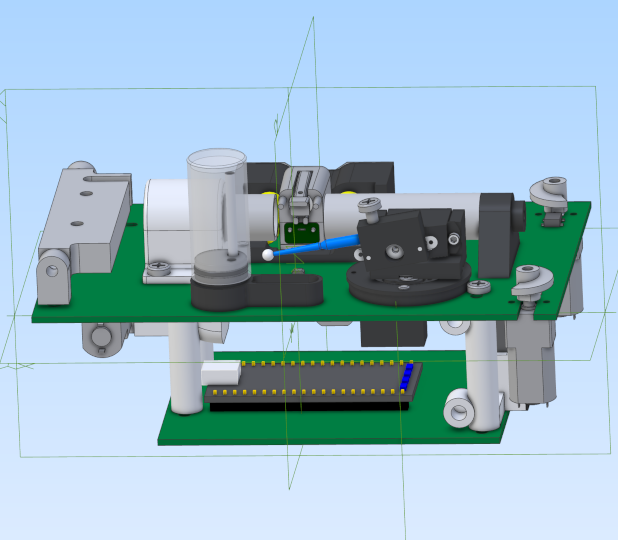

The solution was to create a stepwise concentration change by switching between air drawn directly from the target and filtered ambient air. At the same time, bees are sensitive to sudden changes in airflow volume, so the system had to maintain a constant flow rate while sharply changing vapour concentration.

This was achieved using a standard respirator filter cartridge and two synchronised RC servos controlling air diverter valves. Switching both valves simultaneously allowed concentration changes without disturbing airflow volume.

Bee training

In addition to the detection device, I also developed a concept design for an automated bee training system, intended for forward deployment in security and defence applications.

Built into a rugged 6U flight case, the system incorporated up to four parallel training stations and a robotic handling mechanism for more than 500 beeholders. This allowed training rates of up to 80 sniffer bees per hour.

A prototype training station was built and tested, achieving training results comparable to labour-intensive manual training performed by Inscentinel scientists.

What happened next

The trial results were encouraging, while also identifying areas requiring further refinement. Progressing the system beyond the prototype stage would have required additional investment, which was not secured, and development therefore did not continue toward commercial deployment.

In parallel, exploratory trials demonstrated applicability to other targets, including detection of drugs of abuse, food safety screening and selected clinical diagnostics.

What this project illustrates

This project required translating a biologically inspired laboratory concept into a field-deployable system under severe constraints. It involved system-level architecture, sensor interpretation, airflow engineering, embedded electronics, and practical usability — and demonstrates how early design decisions driven by real-world constraints shape the viability of complex sensing systems.